Today I had the pleasure of presenting with Claire Hill on what a research-informed classroom actually looks like. Both Claire and I share a vision of using research to guide effective classroom practice in our departments but also as a way to reduce unnecessary workload by focusing on the things that are more likely to really make a difference. Link to the PowerPoint slides here.

I started by talking about the fact that in the first years of my teaching I did not have a good definition of learning – which now seems pretty remarkable given that I was in the job of getting students to learn stuff… However, if we take this notion from Kirschner, Sweller and Clark (2006) it’s a bit of a game changer. If we make long-term learning the goal of our teaching then it calls into question all sorts of practices which have long been established. For example, the model of massing practice in half-term long units (sometimes focusing on knowledge/skills which will never be revisited) is perhaps not the best model for learning.

Such massed practice is great for performance of learning – your students will probably appear to know a lot about a topic by the end of the unit. However, this gives us a false sense of security because it’s so easy for students to appear as if they’ve learnt something if we’ve only just finished teaching it.

The truth is that when teachers try to facilitate learning by making it as easy as possible they’re increasing the immediately observable short-term performance but that often comes at the expense of important long-term retention. In short, we often seek to eliminate difficulties to the detriment of long-term learning.

I think it’s important that I say here that I completely understand why, with certain in-school accountability measures, teachers do strive to make learning as easy as possible to increase perceived performance or perceived progress. School leaders need to understand that excessive data drops/captures/trawls are having a negative effect on learning. In seeking to measure performance, presumably to implement targeted intervention, they are actually making progress and learning LESS likely.

So how can we ensure that the time and effort put into lessons, by both students and teachers, is resulting in long-term learning and not just performance?

Well Bjork suggests introducing what he terms ‘desirable difficulties’. Bjork argues that by introducing these ‘desirable difficulties’ we can improve the long-term retention of what students are learning. As teachers, our goals should be long term and not about what a student has leant by the end of the lesson, unit or key stage.

To appreciate why difficulties might actually be desirable, we must first make a distinction between performance and actual learning itself.

Performance: Observable during learning and testing

Learning: A long-term process that is difficult to measure

We need to separate performance and learning and prioritise the latter in our classroom.

Bjork begs the question that ‘if the research picture is so clear, why then are massed practice, excessive feedback, fixed conditions of training, and limited opportunities for retrieval practice such common features’ in the classroom?

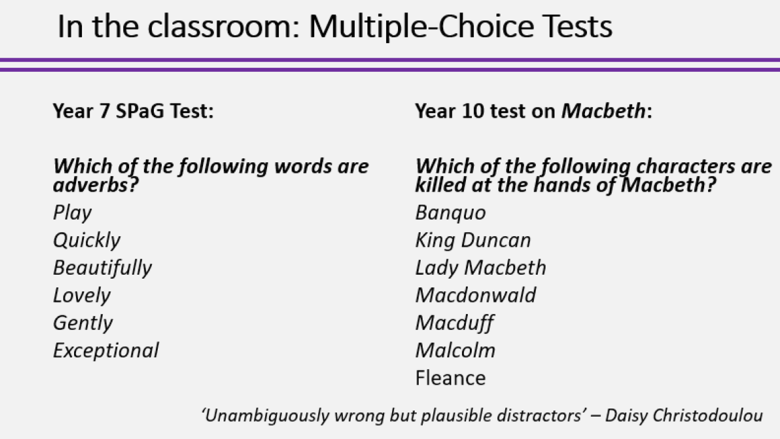

Claire then began to talk about the classroom application of this research about learning and desirable difficulties by talking about using multiple-choice tests to exploit the testing effect and to increase the durability, and students’ ability to recall, what they’ve learnt.

With the new linear specifications and the vast body of knowledge that needs to retained, it is no longer an option to teach a text or topic in September of year 10 and then only come back to this in the lead up to exams in year 11. It is little wonder that with this approach the period between January and May of year 11 is oftentimes filled with intervention and revision sessions because students have not revisited or revised half of the topics since year 10.

No revision happens every lesson through different forms of retrieval practice with students being pushed to retrieve knowledge from things they learnt in a previous topic, month, term or year. This retrieval practice is low stakes and can take many forms.

Multiple choice questions (MCQs), like those on the slide, not only allow for retrieval practice but also serve to give teachers an insight into which students still have misconceptions or misunderstandings. For example, if a student identifies that ‘lovely’ is an adverb because it ends in ‘ly’ then that’s a misconception that can be identified through MCQs and addressed. MCQs, once created, can be used, refined and used again. Your team can work together to generate these and, if you have a team with varying experience, your more experienced teachers can really inform the creation of these because they’ll know the misconceptions that students will likely make.

I spoke briefly about how providing students with a knowledge organiser is a powerful way to be explicit about the knowledge all students are expected to know. This knowledge can then easily be tested in the form of 5-a-Day Starters which include a mix of questions from topics covered so retrieval is distributed. They’re also a great way to establish a routine at the start of lessons where students are expected to ‘get in and get on’ with their learning.

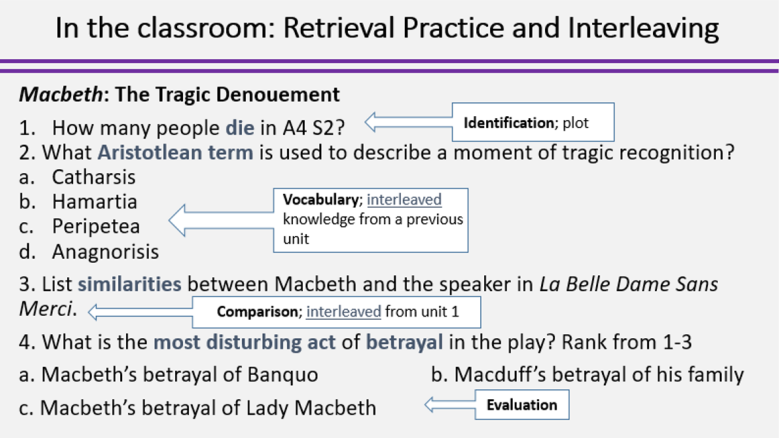

Claire then shared the next step in creating retrieval practice questions which is to consider how these might be used to really extend students’ thinking and to include comparison and evaluation as well as recall. The example here is adapted from one used by Claire’s 2iC and this structure is now followed for a series of questions on different texts and for different year groups as a further development to her department’s work on retrieval practice. Creating a bank of these questions by dividing texts across members of the department has been a good way to save time and share workloads whilst also offering teachers the opportunity to really think about students’ possible misconceptions and ways to further interleave topics across the curriculum.

Reducing workload is at the centre of nearly every policy and practice Claire introduces. Claire has not marked a single piece of homework for over four years and never intends to again. This doesn’t mean that students in Claire’s school don’t do homework – they absolutely do and it is checked in lesson along with seeing just how well the homework has been completed. However, most homework is checked through retrieval practice in of the many forms already mentioned which does not require teacher marking.

However, essay homework is dealt with slightly differently. When students write an essay for homework, Claire will take it in and have a look over it but won’t give any feedback. The reason being that Claire is unable to control the conditions in which the homework has been completed – any feedback given on homework is not going to be as accurate or helpful as feedback on a timed piece written in lesson. Claire will, instead, mark their essays written in lesson and give feedback before asking students to use the feedback from the lesson essay to improve their homework essay thereby transferring the feedback to a new piece of work. The idea behind this is based on Dylan Wiliam’s assertion that the ‘main purpose of feedback is to improve the student [to help] the student do a better job next time’. By using this model, Claire can see that they are transferring their feedback to another piece of work and therefore they are more likely to be able to apply this to their next piece of work.

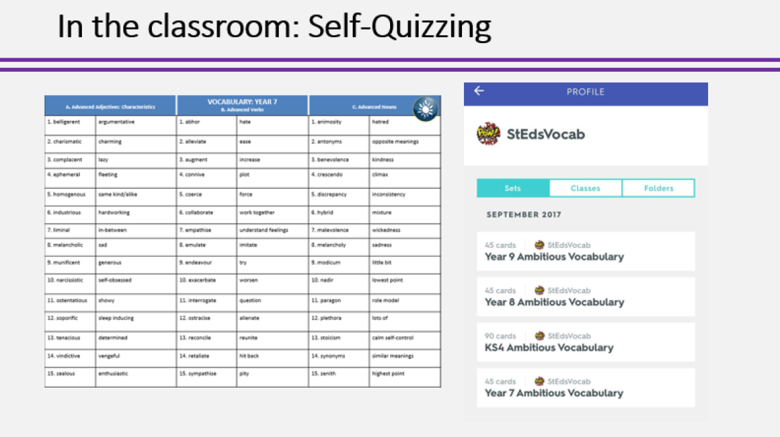

I then spoke about the best thing I’ve introduced for homework at both KS3 and KS4: self-quizzing. This idea was inspired by reading Joe Kirby’s chapter in ‘Battle Hymn of the Tiger Teachers: The Michaela Way’ entitled ‘Homework as Revision’. Not only does it complement my department’s approach to homework (activities which have high value but require no marking) but students’ knowledge has improved as well as their confidence.

Students are expected to spend 30 minutes every week self-quizzing on a section of their knowledge organiser. They do this by recalling, as accurately as they can, everything they can and, once finished, checking their work against the knowledge organiser and using a different coloured pen to fill in gaps and correct errors. This way, progress can easily be seen and it’s incredibly quick and easy as a class teacher to check that the homework has been completed by expecting students to have their books open on their desks and quickly walking around the room.

It’s also a great revision activity in the classroom to give students a blank knowledge organiser or a mostly blank knowledge organiser to fill in. Students really enjoy the challenge and it highlights very clearly to them where their gaps in knowledge are.

Students at KS3 an KS4 in my school also self-quiz on their ambitious vocabulary using the Quizlet App (or look, cover, write, check if they haven’t got access). Students are encouraged to spend a few minutes every day self-quizzing on their vocabulary.

In his New Theory of Disuse (1992), Bjork theorises that memories don’t decay. He suggests that it’s not that memories disappear but that we stop being able to retrieve them. You could liken this to having a shoe cupboard full of shoes and knowing there’s a certain pair in there but being unable to dig them out. The shoes still exist but you can’t find them under the mountain of other shoes!

What’s really exciting about Bjork’s ideas is that it suggests we have an infinite long term memory store – there’s potentially no limit to the amount of knowledge we could know but we need to get better at retrieving that information.

However, there’s a barrier to getting things into our long term memory: our working memory. Our working memory is limited and there’s research to suggest that our personal working memory limit is fixed and there’s not much we can do about that. We need to navigate the bottle neck of working memory to get more stuff into long term memory.

We need to reduced the extraneous cognitive load in lessons in order that students can manage the intrinsic cognitive load of what we’re trying to teach them. We can’t change the intrinsic challenge of a text like Jane Eyre (and we certainly shouldn’t avoid teaching it because it’s challenging) but we can change our lessons to reduce the extraneous cognitive load which will be taking up students’ working memory.

For example, we need to ensure that students can see the board easily e.g. by seating them in rows. We need to have periods of silence in lessons so that students can concentrate on their deliberate practice. We need to give students enough time to complete tasks. We also need to avoid flooding our PowerPoint slides with lots of text and then talking over it.

Dan Willingham argues that ‘memory is the residue of though’ and that students will remember what they think about. I shared an example of a lesson that almost certainly ensured students did not remember what they were meant to though they probably do remember spending an English lesson sticking their hands in kidney beans and mash potato… We must be mindful of what students are spending lesson time thinking about and directing that very carefully to what we want them to be thinking about.

All teachers can probably think of an example from their teaching career where they’ve done something similar – it speaks of a zeitgeist of teaching (circa 2006 onwards but perhaps earlier) where the primary goal of lessons seemed to be engagement and ‘wow’ moments. Outstanding gradings were awarded in lessons where poor proxies of learning were evident (e.g. minimal teacher talk) and questionable practices abounded such as discovery learning and group work (de Bono’s thinking hats anyone?).

We must work towards using the most effective methods in lessons such as modelling. There’s lots of evidence to suggest the power of metacognition and modelling. Spending time modelling though processes and showing students how to construct an answer is an extremely powerful lesson activity. Live modelling was a regular feature of lessons before PowerPoint (the temptation to show ‘one I made earlier’ is strong) and it’s something we need to do more of. We need to show students that it’s a complicated thing to construct an essay response but by modelling the process of working through that we are empowering students to do the same whilst also providing them with a model of excellence.

I’ve bought everybody in my team a visualiser and we use them all the time both to model and look at student work with the class.

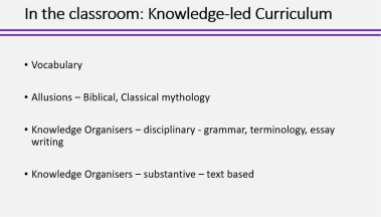

Claire talked about the principles of designing a knowledge-led curriculum and distinguishing between disciplinary knowledge and substantive knowledge. A more detailed blog to follow on this…

When designing a curriculum it’s important not to see learning as discrete bundles that can be tied up at the end of a lesson or unit. We must also strive not to be dictated to by the calendar (where’s the logic in a six week unit of work other than because this is how the year is divided up because of holidays?) or by the data monster. Too often we distort the learning process by trying to meet certain deadlines throughout the year.

I talked briefly talked through my curriculum design. In KS3 students cover two main topics a year (a novel and a Shakespeare play) but this is interleaved with poetry lessons, weekly writing challenge lessons and analysis of unseen fiction and non-fiction. The rainbow strips across the top are threshold concepts which essentially represent the idea that that we are doing all of the things all of the time rather than massing practice into blocks.

At KS4, students sit their English Language exam at the end of year 10 but they study two of the Lit texts. In year 11, from September until Christmas the other two texts will be studied so that after Christmas, though commonly after February half term due to PPE disruption, all four texts are interleaved in the course of study.

Here’s a the beginning view weeks of a typical KS3 medium term plan. What you can see here is that students don’t have consecutive lessons on the same thing. Initially teachers found this a real challenge and we had to work towards not blocking lessons together but students have never found this difficult or even questioned why they’re studying Animal Farm one day and writing skills the next. This may be because they’re used to bouncing from subject to subject. In their day they might go from studying trigonometry lesson one and then the water cycle period two, running around playing hockey period three before coming to English. The other thing that’s been built into the curriculum is whole lessons for feedback.

I shared an example of the whole-class feedback approach which my department have adopted. Students receive a specific numbered target and a whole class feedback sheet (either printed and/or displayed) that includes praise, common spelling errors and exemplars of great work. It’s so much quicker to mark in this way then laboriously write out individual comments and litter students work with comments/questions. I simply jot down comments on a sheet of paper as I’m marking and then it takes me 5 minutes or so to create a whole class feedback slide with a set of numbered targets specific to that class and what I’ve seen from reading their books.

Feedback lessons are an opportunity for teachers to re-teach and model where necessary and then students spend the rest of the lesson completing a ‘DIRT Task’ that will be specific and actionable – an opportunity to act on their targets either by redrafting a piece of work or completing a new task where they can demonstrate that they’ve acted on the feedback and made progress. Students will then draw a yellow box around this.

Claire shared this extract from Carl Hendrick and Robin Macpherson’s book ‘What Does This Look Like In The Classroom’. The highlighted section clearly questions the common practice in school of writing lengthy summary comments at the end of a piece of work. Not only are these time-consuming but also largely ineffective.

Sharing WWWs for the whole class is far more effective, and efficient, than giving every student a WWW comment. Not only will one document save time in writing, but it also means every student can see the possible ideas they could have used and gives an opportunity to re-teach some of these ideas if not may students used them in their work.

In terms of teacher input, Claire will read through the work and add codes linked to EBI tasks, at first this will be next to where students need to include more detail or make changes, but later it will just be at the end of the work and students work out where their improvements would be best added. As suggested by Daisy Christodoulou, the tasks are ‘actionable’ and students have ‘something they can go away and do in response to it’. Therefore, instead of writing ‘EBI: Analyse in more detail’ for the 60-70% of the class you may need to use that comment for, you simply write one number and give students a specific task to complete i.e. ‘pick out key words such as ‘milk’ or ‘gall’ and analyse in more detail, considering the connotations of those words’. The next time a student completes a similar piece of work, ask them to prove that they will not need the same target as last time, by asking them to highlight evidence that they have met this target in their new piece of work.

We wanted to our presentation with the exciting news that we are working on a book together. Leading from the Middle: A Guide to Effective Middle Leadership will be published later this year by John Catt and is available to order now here.

Really enjoyed this session. Thanks very much

LikeLike

Thanks Charlotte and thanks for coming!

LikeLike

What a fantastic post – thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks Rik

LikeLike

Fantastic! Thanks for sharing your real world examples.

LikeLike

Thanks Steven

LikeLike